- Joined

- Oct 18, 2005

- Location

- Chicago Burbs

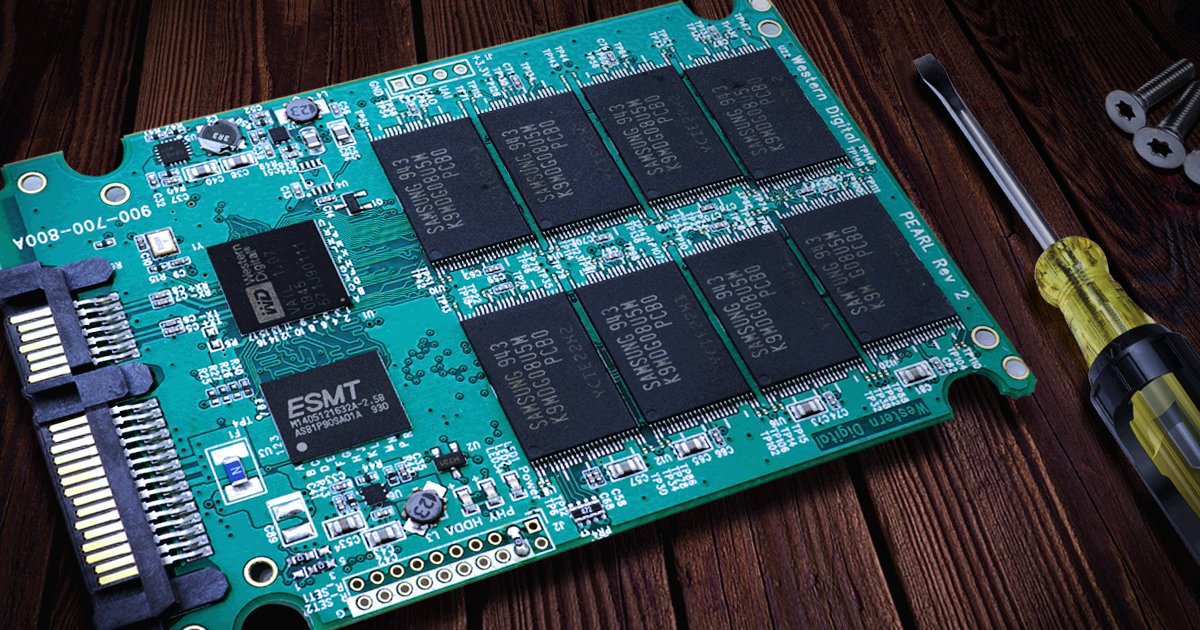

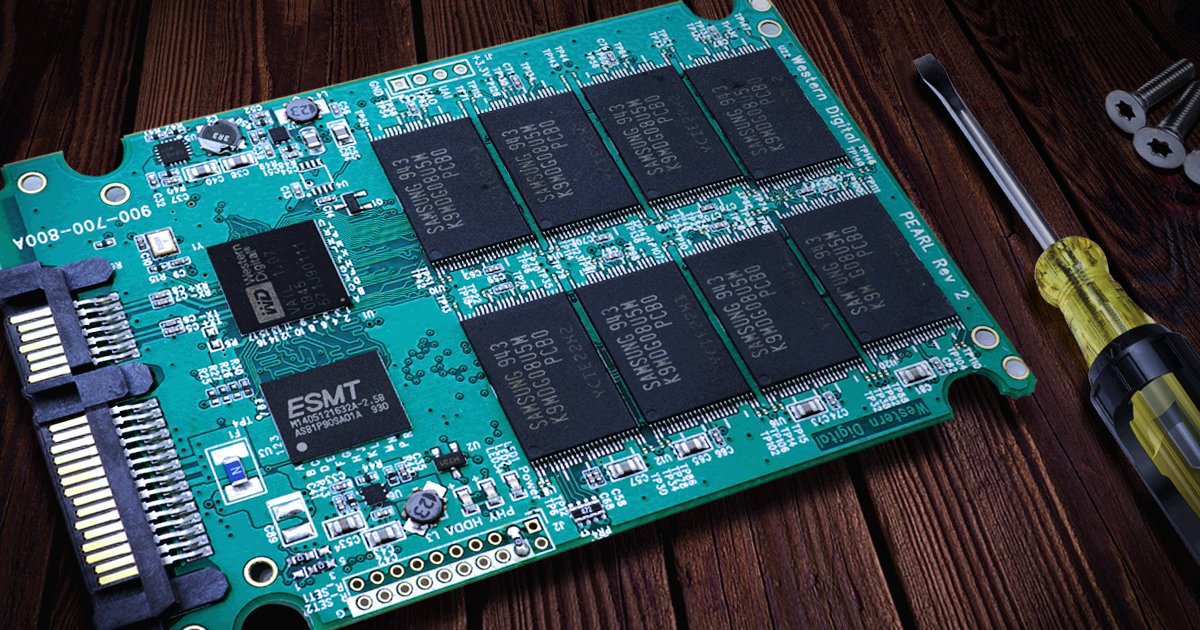

So apparently a big reason SSDs like to die suddenly is that they have on their storage media a reserved area used to manage the rest of the space with things such as translation tables. This area, or parts of it, cannot be wear-levelled/remapped and there is no health indicator for it. As a result, regardless of the state of the rest of the media, if this system area ends up getting rewritten in some spots too much, as soon as any part of that area fails, it's game over for the entire device. I will quote this blog post

blog.elcomsoft.com

blog.elcomsoft.com

If indeed this is the case, it would certainly motivate me to take steps to slow down the march toward such failures on OS drives or important work drives to avoid running into unexpected down time, such as moving, as much as possible, temporary files/cache operations either to separate throw-away SSDs or to an HDD.

I was bothered quite a bit by just how much data is constantly being written on the OS drive by all sorts of programs (kind of silly they'd need to do that all day long if you ask me), but when I did the math, it would take a large number of years before it came anywhere close to the supposed rewrite capacity. But that sounded just too good to be true... and indeed, it appears it WAS too good to be true, because the general storage media wear-down isn't where the true danger lies.

Accurate?

Why SSDs Die a Sudden Death (and How to Deal with It)

NAND flash memory can sustain a limited number of write operations. Manufacturers of today’s consumer SSD drives guarantee up to 1200 write cycles before the warranty runs out. This can lead to the conclusion that a NAND flash cell can sustain up to 1200 write cycles, and that an SSD drive can actua

Why SSD Drives Fail with no SMART Errors

SSD drives are designed to sustain multiple overwrites of its entire capacity. Manufacturers warrant their drives for hundreds or even thousands complete overwrites. The Total Bytes Written (TBE) parameter grows with each generation, yet we’ve seen multiple SSD drives fail significantly sooner than expected. We’ve seen SSD drives fail with as much as 99% of their rated lifespan remaining, with clean SMART attributes. This would be difficult to attribute to manufacturing defects or bad NAND flash as those typically account for around 2% of devices. Manufacturing defects aside, why can an SSD fail prematurely with clean SMART attributes?

Each SSD drive has a dedicated system area. The system area contains SSD firmware (the microcode to boot the controller) and system structures. The size of the system area is in the range of 4 to 12 GB. In this area, the SSD controller stores system structures called “modules”. Modules contain essential data such as translation tables, parts of microcode that deal with the media encryption key, SMART attributes and so on.

If you have read our previous article, you are aware of the fact that SSD drives actively remap addresses of logical blocks, pointing the same logical address to various physical NAND cells in order to level wear and boost write speeds. Unfortunately, in most (all?) SSD drives the physical location of the system area must remain constant. It cannot be remapped; wear leveling is not applicable to at least some modules in the system area. This in turn means that a constant flow of individual write operations, each modifying the content of the translation table, will write into the same physical NAND cells over and over again. This is exactly why we are not fully convinced by endurance tests such as those performed by 3DNews. Such tests rely on a stream of data being written onto the SSD drive in a constant flow, which loads the SSD drive in unrealistic manner. On the other side of the spectrum are users whose SSD drives are exposed to frequent small write operations (sometimes several hundred operations per second). In this mode, there is very little data actually written onto the SSD drive (and thus very modest TBW values). However, system areas are stressed severely being constantly overwritten.

Such usage scenarios will cause premature wear on the system area without any meaningful indication in any SMART parameters. As a result, a perfectly healthy SSD with 98-99% of remaining lifespan can suddenly disappear from the system. At this point, the SSD controller cannot perform successful ECC corrections of essential information stored in the system area. The SSD disappears from the computer’s BIOS or appears as empty/uninitialized/unformatted media.

If the SSD drive does not appear in the computer’s BIOS, it may mean its controller is in a bootloop. Internally, the following cyclic process occurs. The controller attempts to load microcode from NAND chips into the controller’s RAM; an error occurs; the controller retries; an error occurs; etc.

However, the most frequent point of failure are errors in the translation module that maps physical blocks to logical addresses. If this error occurs, the SSD will be recognized as a device in the computer’s BIOS. However, the user will be unable to access information; the SSD will appear as uninitialized (raw) media, or will advertise a significantly smaller storage capacity (e.g. 2MB instead of the real capacity of 960GB). At this point, it is impossible to recover data using any methods available at home (e.g. the many undelete/data recovery tools).

If indeed this is the case, it would certainly motivate me to take steps to slow down the march toward such failures on OS drives or important work drives to avoid running into unexpected down time, such as moving, as much as possible, temporary files/cache operations either to separate throw-away SSDs or to an HDD.

I was bothered quite a bit by just how much data is constantly being written on the OS drive by all sorts of programs (kind of silly they'd need to do that all day long if you ask me), but when I did the math, it would take a large number of years before it came anywhere close to the supposed rewrite capacity. But that sounded just too good to be true... and indeed, it appears it WAS too good to be true, because the general storage media wear-down isn't where the true danger lies.

Accurate?